Disasters like Hurricane Ian can affect academic performance for years to come

Tips

Carl F. Weems, Iowa State University

When leaders at a middle school in New Orleans asked me to help students who were struggling after the city had been struck by Hurricane Katrina, we didn’t see eye to eye.

They wanted me to focus on helping the children overcome test anxiety. Their concern was enabling the children to pass a high-stakes standardized test.

As a developmental psychologist who specializes in how children respond to adverse events that cause stress and anxiety, I – and my colleagues – had something else in mind. We wanted to learn more about the severity of the children’s trauma. We wanted to know how they were coping with any lingering effects of having their lives uprooted by the hurricane. Our objective was to develop an intervention to reduce their overall anxiety, not just help kids do well on a test.

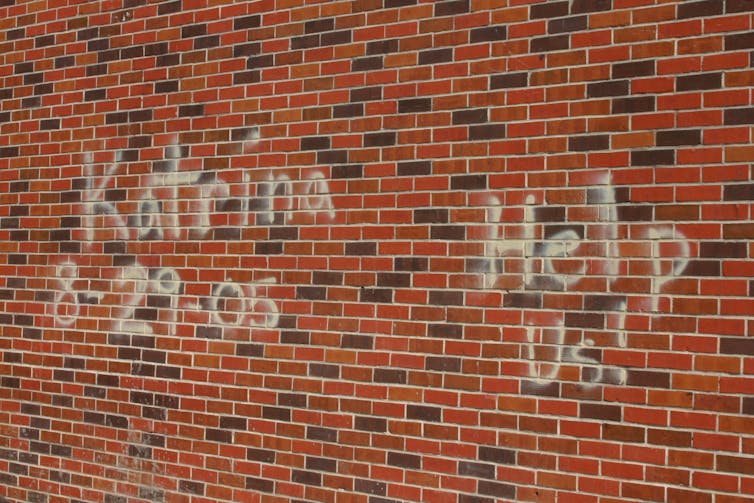

Based on the destruction I saw surrounding the school – which was located in one of the hardest-hit areas of the city – we felt strongly that our cause was the more noble of the two. I reflected on my time in New Orleans in the wake of Hurricane Katrina after I saw how hard Florida had been hit by Hurricane Ian.

For instance, I recalled when I looked out the classroom window in New Orleans seeing the watermarks 8 feet (2½ meters) high on the houses surrounding the school, most of them still boarded up and uninhabited. Only a house here and there had been renovated.

The children were traumatized in many ways: By the high-crime neighborhood they lived in but loved. By the fact that their neighborhood was now partially gone because of damage from the storm. By having to see the hurricane’s devastation every day – even a year after Katrina made landfall in Louisiana on Aug. 29, 2005.

So we asked about screening the kids for post-traumatic stress disorder. School leaders, however, kept stressing the need for the students do well on the standardized tests.

The conflict eventually led me to an important realization: We didn’t have to choose between overcoming text anxiety and PTSD. We could do both. I figured that helping children regulate their emotions while taking a test could also potentially help them regulate their emotions in everyday life.

So began our decade of research into what it takes to rebuild children’s emotional wellness in the years that follow a hurricane.

As Florida officials struggle to get the state’s schools back on track in the wake of Hurricane Ian, we believe our post-Katrina research in New Orleans offers important insights on how to make sure those efforts address the emotional toll the hurricane may have taken on the state’s K-12 students.

A matter of years

One of the most important lessons is that just as it will likely take years to rebuild the infrastructure and homes hit by Hurricane Ian, it could take a similar amount of time to help some children regain a sense of normalcy. My own research – and that of many others – shows that while children are often resilient in the face of disasters, the effects of trauma can be insidious and linger for years to come.

And not all children will be affected the same. Many may have intense and lasting symptoms of anxiety that are stable over time. Others may initially show a few symptoms that get worse or grow as time passes. Some children may show symptoms that evolve over time into other symptoms. Common symptoms include hyperarousal, which is when a kid’s body kicks into high alert, and emotional numbing, which often evolves later and involves difficulty experiencing emotions, usually positive ones.

Our research shows that witnessing disasters and home damage is associated with PTSD symptoms, which may show up as test anxiety and ultimately lead to lower academic achievement.

Because of the variability in how symptoms show up, screening children for distress is warranted. School-based screenings and interventions that help children regulate their emotions may be beneficial for all youths in hard-hit areas. School-based screenings may also be warranted both in the immediate aftermath and over the long term. The screenings can help to further identify youths in need of referral to more intensive services.

In 2010, my colleagues and I suggested children affected by disasters be screened for anxiety related distress. For my colleagues and me, it’s heartening to know that the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, an independent volunteer panel of experts in disease prevention and evidence-based medicine, has recommended an even broader approach: anxiety screenings for all children and adolescents ages 8-18, not just those affected by disasters. It will be particularly critical to follow this policy recommendation in areas affected by Ian and other disasters.

Targeting test anxiety

In our post-Katrina research, we also found that targeting test anxiety through an intervention was associated with reduced PTSD symptoms.

When students experience PTSD, they are more likely to experience test anxiety. And when they experience test anxiety, they are less likely to score well on tests, our research shows. Indeed, scientists and now many policymakers accept that childhood exposure to adverse or traumatic events may have negative effects on the developing brain.

Therefore, if schools want to help students do better, my research suggests they should focus on helping kids learn to regulate their anxiety. One way to do this is to use cognitive behavioral therapy, which is a treatment that helps people identify and change negative thought patterns that affect their behavior and emotions. This involves a number of techniques, such as helping kids directly face their fears and difficulties – in this case, tests – instead of avoiding problems. Prior research has found a link between students with PTSD and “school refusal” behavior – that is, refusing to go to school.

Another technique is called progressive muscle relaxation. This technique involves tensing and then releasing all of the muscles in your body, progressively from your toes to your face. Another technique was deep breathing.

Test-anxious kids who were taught these techniques after Katrina saw their grades improve an average of one letter grade, in this case from mostly C’s to mostly B’s. Our research also suggest these techniques may help prevent long-term difficulties. The same techniques could be useful in Florida as well.![]()

Carl F. Weems, Professor and Chair, Human Development and Family Studies, Iowa State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Comments (5)

Best Company Reply

- Ali Tufan

- 2 days ago

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Fusce vel augue eget quam fermentum sodales. Aliquam vel congue sapien, quis mollis quam.Because Other Candidates

- Martha Griffin

- 23 August 2018

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Fusce vel augue eget quam fermentum sodales. Aliquam vel congue sapien, quis.Aldus PageMaker including versions Reply

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Fusce vel augue eget quam fermentum sodales. Aliquam vel congue sapien, quis mollis quam.