Divesting university endowments: Easier demanded than done

Tips

Campus protests expressing solidarity with the Palestinian people and objecting to Israel’s military campaign in Gaza include many calls for universities and colleges to divest – a word that basically means sell – any of their assets that are tied to Israel or connected to companies supplying weapons and technology to Israel’s government. The Conversation U.S. asked Todd L. Ely, a University of Colorado Denver public administration scholar, to explain the challenges of meeting this demand.

What are endowments?

Endowments are pools of assets that originally come from donations. Nonprofits and some public organizations invest those assets, which grow over time, and disburse a small percentage of them annually to support their missions. Nearly all nonprofit colleges and universities have endowments, as do hundreds of public institutions of higher education – some through associated nonprofit foundations.

U.S. college and university endowments had around US$1 trillion in assets as of the middle of 2021 – the most recent comprehensive data available.

This wealth is highly concentrated. Nearly half these assets belonged to the 20 largest endowments in 2021. Endowments worth $40 million or less are more typical and around 95% colleges and universities have less than $1 billion in their endowments.

Endowment managers generally see making money as their primary objective and large amounts of these assets are subject to restrictions due to donors’ preferences.

Columbia University’s $13.6 billion endowment, for example, as of 2023 was split among more than 6,200 different funds and about two-thirds of the assets in its endowment were subject to donor-related limitations.

Because colleges and universities aim to preserve their endowments to support their operations for the foreseeable future, they typically spend about 5% of those assets per year on student financial aid and assorted programs to supplement what they can afford from their other revenue – primarily tuition, fees for housing and food, as well as state funding for public institutions. Columbia’s endowment, for example, disbursed $679 million during its 2023 fiscal year.

Many protesters have said they object to their tuition dollars being in an endowment with financial ties to Israel. But that’s not how endowments work. Universities and colleges typically spend all the money they receive from tuition on core operations. They supplement those funds with revenue from other sources – including their endowments.

How much information about endowments is made public?

Because it’s unclear how much of these assets are tied to Israeli companies or the Israeli military, many protesters are calling on their colleges and universities to disclose more information about what’s in their endowments.

While universities and colleges typically release their audited financial statements annually, details about their endowments’ holdings are hard to find for several reasons.

First, professionally managed investments change so frequently that what’s in an endowment is a moving target. Periodic reporting at best reflects a historical snapshot.

Second, higher education endowments are complex. Timely and detailed reporting of investments, while desirable for oversight, can reveal the secret proprietary strategies of endowments and their investments, including alternative investments like hedge funds.

Third, colleges and universities are increasingly hiring outside asset managers and hedge funds to manage their endowments. Agreeing to keep quiet about those investments may be required due to the proprietary nature of those deals.

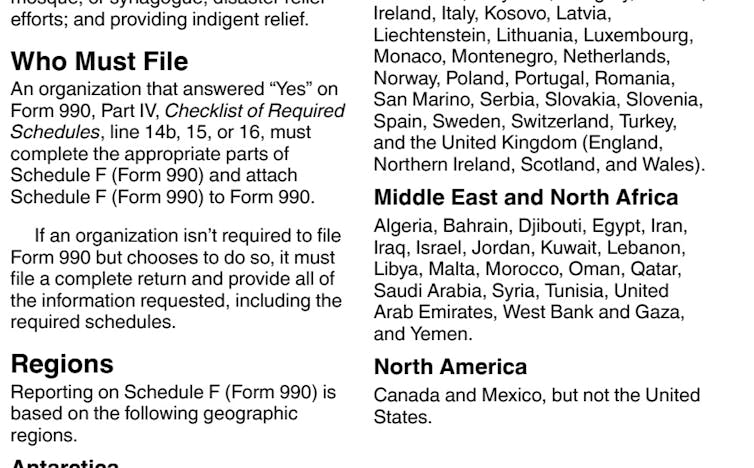

Some information about endowments does show up in 990 forms, which are informational returns charities file annually with the Internal Revenue Service and are made public. That form’s Schedule D includes the endowment’s size, its administrative expenses and the general restrictions it faces.

Although the forms require the disclosure of “Activities Outside the United States” in Schedule F, the highest level of detail required is the region of those investments. In other words, any investments in Israeli companies might be lumped together with investments in corporations based in Qatar or Lebanon.

Are there legal obstacles?

Universities and colleges might not always be free to divest their endowments.

When it comes to severing ties with Israel, laws in at least 38 states discourage such actions by public universities and sometimes include banning that kind of divestment by outlawing adherence to the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement that has sought to pressure Israel for nearly 20 years.

Other state laws more broadly limit the use of environmental, social and governance (ESG) investment practices by public institutions.

For example, officials at The Ohio State University have cited their state’s laws when they’ve told protesters they can’t sever ties with Israel.

There is also a law that governs the investment and use of funds by nonprofits in nearly all states: the Uniform Prudent Management of Institutional Funds Act. This measure mandates a “prudent” approach to investment that can be interpreted as attempting to maximize an endowment’s growth.

However, some divestment advocates argue that colleges and universities have a moral duty to divest in certain cases based on those same laws – even if it means an endowment will potentially grow more slowly.

Is divestment from Israel feasible?

To be sure, many colleges and universities have agreed in recent years to students’ demands for divestment from industries that include tobacco, fossil fuels, private prisons and firearms. About 40 years ago, hundreds of schools divested from companies doing business in South Africa before the fall of its apartheid government.

But it would be hard to determine what specific assets would need to be sold off and then avoided for the foreseeable future if today’s protesters were to prevail.

No matter the focus of these campaigns, divestment takes political will, time and effort to implement. It also increases transaction costs, reduces access to certain investment products, and can take a long time due to how higher ed endowments are invested.

That’s partly because endowments generally don’t just include large amounts of stocks and bonds. To reduce risks, they are increasingly invested in mutual funds and other assets that are made up of many different securities. Outsourcing management of portions of their portfolios to private equity firms leads to other complications.

“The University has no discretion as to withdrawal of its investment in private equity and real asset funds,” Columbia University noted in its 2023 audited financial statements. “Distributions are made when sales of assets are made within the funds. In general, the remaining life of these private equity and real asset funds is up to 12 years.”

There’s yet another concern for colleges and universities: many of their biggest donors have made it clear that they oppose divestment from Israel. In some cases, those donors have said they’ll stop giving to schools that sever ties with Israel as the protesters demand.

Does divestment work?

Whether divestment works probably depends on its advocates’ goals.

If they want to impose meaningful financial losses on specific companies, industries or countries, research indicates that they’re bound to fail for several reasons.

While many college and university endowments are large by most standards, they aren’t necessarily big enough to move financial markets, especially since their investments are diversified.

Also, when a university does own shares in a targeted company, selling that stock simply transfers the ownership to a buyer who is less concerned about the social considerations.

Maintaining ownership and taking a more active investor advocacy role might be an alternative to divestment.

But if the goal is to raise awareness about a cause, then divestment may make a difference – even if it’s hard to measure.

On May 9, 2024, Union Theological Seminary became the first U.S. higher education institution to announce that it would divest its endowment from investments tied to Israel’s military operations. The seminary’s board used this occasion to emphasize that it strives to “not financially support damaging and immoral investments” – making it a good example of the symbolic rather than financial purposes of divestment efforts.

How can colleges and universities heed student demands?

A few colleges and universities have found ways to engage productively with protesters, sometimes even resulting in the amicable end of encampments.

Increasing engagement opportunities for students and the broader academic community around endowments and other institutional investments may provide an outlet to address current and future disputes.

Brown University, Northwestern University and the University of Minnesota appear to be taking this approach.

Some college and universities have promised to consider divestment demands at a future date and disclose more information about what’s in their endowments. Making those pledges has helped keep the peace while guaranteeing that this issue will remain on the agenda in the 2024-2025 academic year.

This article was updated on May 10, 2024, with Union Theological Seminary’s divestment announcement and on May 15 to clarify the restrictions in most states that could limit the divestment of assets tied to Israel.![]()

Todd L. Ely, Associate Professor of Public Administration; Director, Center for Local Government, University of Colorado Denver

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Comments (5)

Best Company Reply

- Ali Tufan

- 2 days ago

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Fusce vel augue eget quam fermentum sodales. Aliquam vel congue sapien, quis mollis quam.Because Other Candidates

- Martha Griffin

- 23 August 2018

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Fusce vel augue eget quam fermentum sodales. Aliquam vel congue sapien, quis.Aldus PageMaker including versions Reply

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Fusce vel augue eget quam fermentum sodales. Aliquam vel congue sapien, quis mollis quam.