What do molecules look like?

Tips

Christine Helms, University of Richmond

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to [email protected].

What do molecules look like? – Justice B., age 6, Wimberley, Texas

A molecule is a group of atoms bonded together. Molecules make up nearly everything around you – your skin, your chair, even your food.

They vary in size, but are extremely small. You can’t see an individual molecule with your eyes or even a microscope. They are 100,000 times smaller than the width of a hair.

The smallest molecule is made of two atoms stuck together, while a large molecule can be a combination of 100,000 atoms or more. A molecule can be a repeat of the same atom, such as the oxygen molecules we breathe, or can be made up of a variety of atoms, such as a sugar molecule made of carbon, oxygen and hydrogen.

But what do molecules look like? It all begins with their building blocks: atoms.

Opposites attract

The particles of matter that make up an atom are not all the same. They can have a positive charge, a negative charge or no charge. Scientists call them protons, electrons and neutrons.

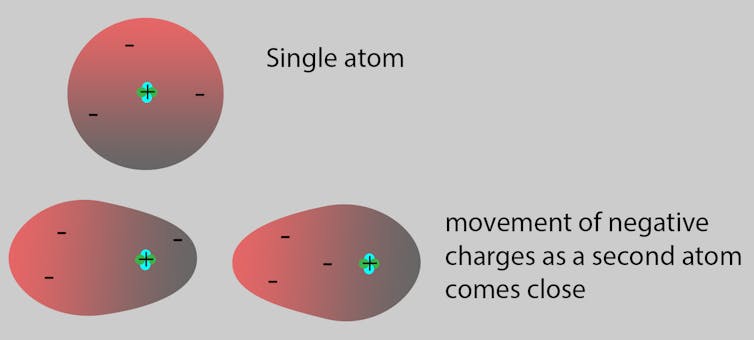

Neutrons with no charge and protons with a positive charge form the heavy center of the atom. The negatively charged electrons surround this small center.

As atoms approach each other to potentially join and make molecules, the negative electrons in one atom are attracted to the positive protons in the other, and vice versa. Both atoms adjust themselves accordingly.

You can compare it to trying to choose a seat in a classroom. There are some rules. For example, you have to stay in the classroom and you cannot sit on top of someone. Following those rules, you might try to sit next to your friends and far from your enemies. Finding the perfect position so everyone in the class is happy is similar to finding the perfect position for the atoms in a molecule. Sometimes, atoms cannot find a happy arrangement and no molecule is formed.

Seeing the unseeable

If molecules are too small to see with your eyes or even a powerful microscope, how do scientists see them? The answer is they have developed special tools to do it.

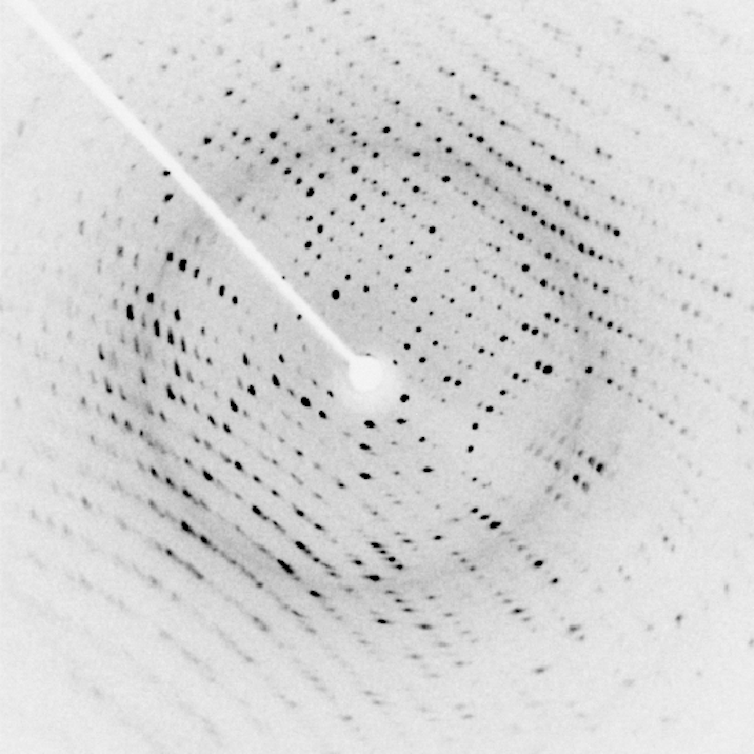

One tool uses X-rays, which you might know about since doctors use them to see bones in the body. X-rays are a type of light that human eyes can’t see, like ultraviolet or infrared light.

When scientists shoot X-rays at molecules, some bounce off. Scientists can record these rebounding X-rays and use their patterns to figure out what individual molecules look like.

In 1912, one of the first molecules seen this way was salt (NaCl) – the molecule that makes up the ingredient we all know and love on french fries.

Scientists have invented other methods to see molecules, too. Similar to how the electrons change their behavior as two atoms come close together, the center of the atom can also change its behavior. A technique called nuclear magnetic resonance detects those changes to the center of the atom and uses them as clues to determine what atoms are close by.

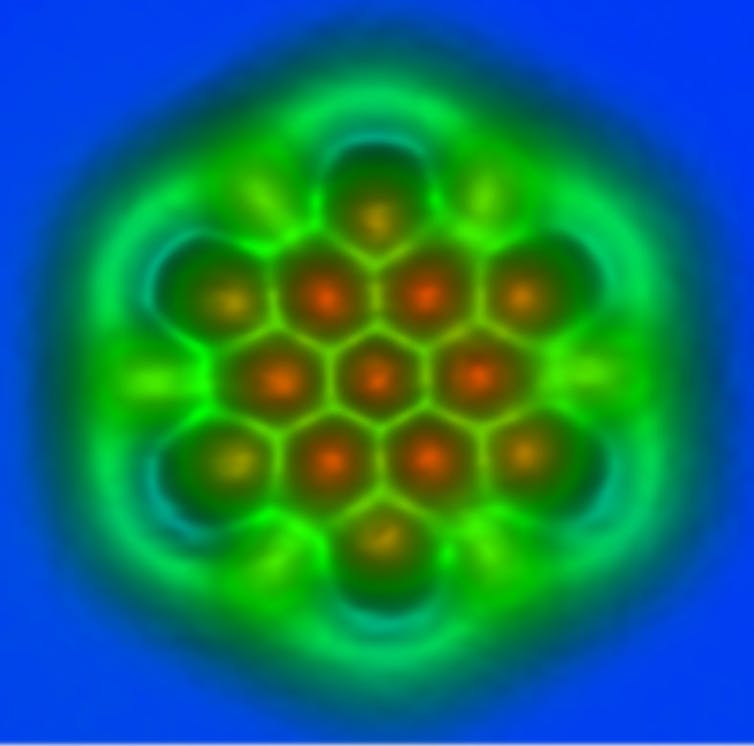

An atomic force microscope works like a flimsy diving board that shakes when you walk and jump on it. But this diving board is extremely small, so small that a negative charge on the end of it will bend it toward the positive center of an atom. Moving this diving board around and watching how it bends can show the location of atoms in a molecule.

One more technique scientists have developed to see molecules is called cyro-electron microscopy. First, scientists freeze molecules to a temperature much colder than snow or ice. Then they shoot electrons at the molecule and collect those that pass through to make an image. This technique won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2017.

All shapes and sizes

So what do molecules look like? They are a grouping of atoms, with the center containing most of the material, while the rest is largely empty space. Each atom has a specific position where it is happy, much like the students in that classroom.

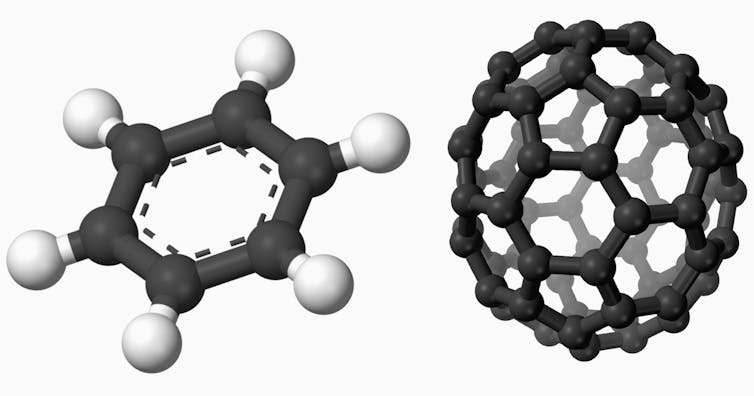

Every molecule is different – some are really different. For example, benzene is flat like a pancake, while fullerene is round like a ball. Penguinone can be drawn to look like a penguin, while other molecules appear to look completely random. But the positions of atoms in a molecule are never random.

While scientists know what a lot of molecules look like, there are some we’re still trying to figure out. Knowing these answers can lead to inventions of new materials and medicines.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to [email protected]. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.![]()

Christine Helms, Associate Professor of Physics, University of Richmond

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Comments (5)

Best Company Reply

- Ali Tufan

- 2 days ago

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Fusce vel augue eget quam fermentum sodales. Aliquam vel congue sapien, quis mollis quam.Because Other Candidates

- Martha Griffin

- 23 August 2018

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Fusce vel augue eget quam fermentum sodales. Aliquam vel congue sapien, quis.Aldus PageMaker including versions Reply

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Fusce vel augue eget quam fermentum sodales. Aliquam vel congue sapien, quis mollis quam.